A Bull in a China Shop

Alibaba and Tencent, choke points between China and the world, but are they ownable? The best lack all conviction and the worst are full of passionate intensity.

Source: Sotheby’s, Zeng Fanzhi & Jack Ma (2014), Paradise

*** Note: For entertainment and informational purposes only. Not investment advice. Please do your own research. ***

The world doesn’t need more underinformed commentary on China. Yet I find myself irresistibly drawn toward the topic, specifically Alibaba and Tencent. I’m like a moth to a falling flaming knife with predictable results.

There’s nothing new here that hasn’t already been written at length over the past year. I’m really just trying to justify to myself why I hold such significant exposure in these companies.

These companies tick off many boxes for me as businesses I would want to hold for the long-term:

Dominant business with high cash flows

Long runway

Moats

Owner operators

Attractive valuations

There are two problems, however.

The first is that you don’t really “own” the company and you have to accept that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is in control and play by their rules.

The second problem is that the U.S. government may inflict collateral damage on these holdings as it prosecutes a trade war against China.

All of this has led to extraordinary negative sentiment in the markets right now when it comes to China.

The bear narrative goes something like this (credit George Soros):

China cannot be trusted. They steal intellectual property. Most of their companies are fraudulent. Their economic metrics and financial statements are likely bogus, and they know it. That’s why China is so committed to opacity, even when the U.S. threatens to cut off access to their capital markets. China has built up an unsustainable debt-fueled house of cards on the verge of collapse. Investors are just throwing money away. That’s what you get when you invest in and support an authoritarian regime that is consolidating control and destroying their most innovative industries and companies in the process. They are turning back the clock on capitalism. They are crushing any entrepreneur who poses a threat to their authority with draconian regulations. The country is slowly bleeding its people away. Your VIE shares are fake shares and everything is ultimately controlled by the Communists anyway. With Xi, this time it’s different. I told you so.

The bull narrative seems to go:

Chinese companies are massive and wonderful businesses. They are too cheap. They are way ahead of the West when it comes to the consumer Internet. The leading players have operations or investments in every relevant category. Their second, third, fourth, n’th tier cities have the populations of small nations on their own. Enormous waves of humanity are moving up the economic ladder and poised to increase their spend. The leading players are incredibly positioned to benefit from that predictable growth trend. The government isn’t so short sighted as to debilitate their leading companies in this way. Charlie Munger, along with other influential and influenced value investors, have invested and doubled down. This too shall pass. But…why take the career risk? Perhaps sit this out until the picture clarifies.

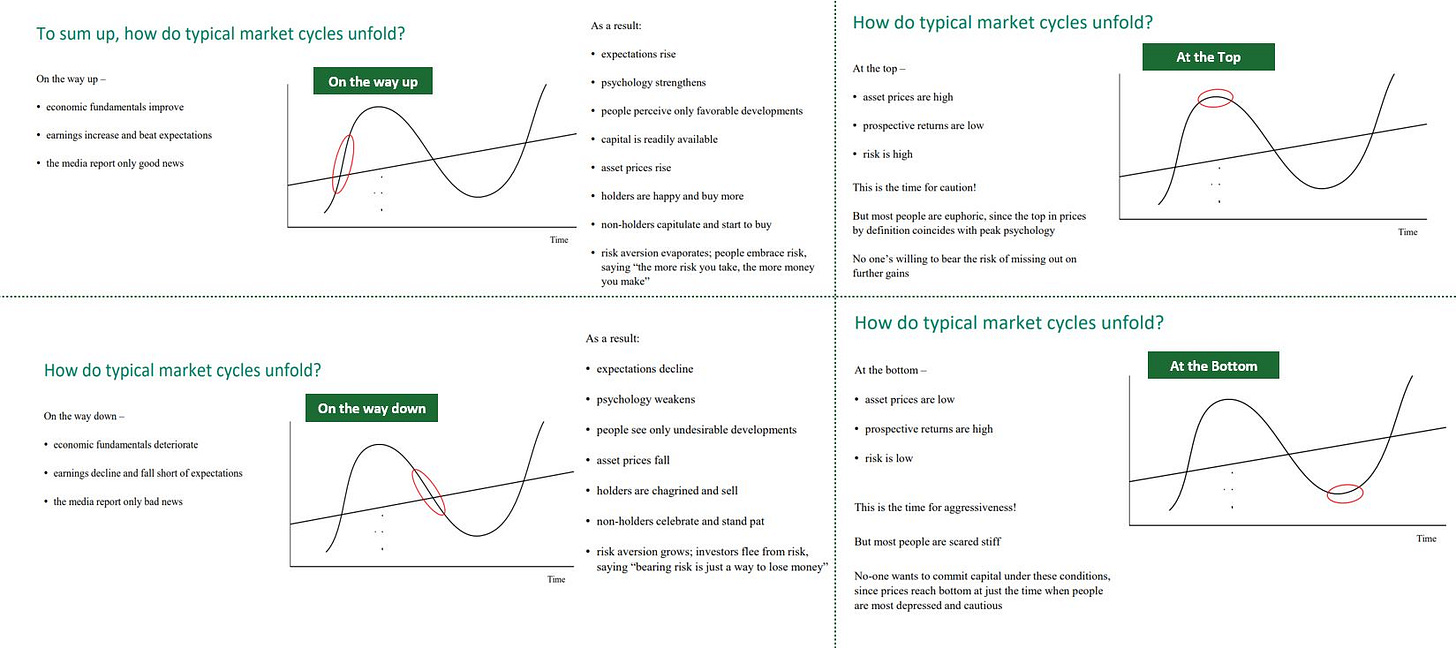

Howard Marks once laid out how the market cycle unfolds and how investor psychology changes.

Source: Howard Marks, Mastering the Market Cycle, via @RamBhupatiraju tweet

The following line marking “At the Bottom” resonates the most for me:

“No one wants to commit capital under these conditions, since prices reach bottom at just the time when people are most depressed and cautious.”

I certainly feel that way.

There’s a ton of opinion out there, and no one knows anything.

I’ve been following Dan Wang to understand the context. The press tends to lean negative when it comes to China. He points to structural considerations to explain why:

“News bureaus are highly concentrated in Beijing, due in part to natural corporate consolidation, but mostly because the government maintains a strict cap on foreign journalist visas. As a result, the bulk of journalists are based in the part of China that has the most politics and the least sense of growth. Everything here is doom and gloom, a fact well conveyed to the outside world. What’s missing are the facts of more pleasant life and higher growth in other cities.”

After considerable allocation of time and money, this is where I’m coming out:

Alibaba and Tencent are incredible businesses with unfair advantages that currently trade at an attractive price.

China regulatory actions on balance appear to be a net positive in the long term for these companies and their shareholders. The regulations are reasonably consistent with their stated goals, unlikely to alter China’s long-term aim to encourage foreign investment, and will probably benefit the incumbents in the long-term.

U.S. regulatory and trade war related actions, however, are a concern. While some of this may be political posturing, only the U.S. is explicitly calling for actions that could lead to outright trading bans.

Risks to Western companies appear to be underappreciated. It certainly should not be isolated to the China side. Western companies are just as susceptible to antimonopoly regulation and trade war crossfire.

The key question: Can I get the return without the control?

I believe the answer is yes.

Foreign investors cannot participate directly and fully in China’s upside, and that is unlikely to change. Getting comfortable with the reality of VIE the relative lack of control is the price of admission.

The lack of control may reflect a deterioration of standards, but that’s been the general trend and bargain to invest in tech companies over the past few decades with the emergence of dual share classes. Exposure comes with a distinct possibility of ruin, but the more painful risk may well be to not participate at all.

In my view, the CCP is acting as the ultimate activist and demanding their platform economies to share their scale benefits. Regulation leads to a healthier environment for sustainable growth. These actions erect barriers to entry in financing and business prospects that benefits the incumbents. It’s short term pain for longer term benefit for all stakeholders. Admittedly, the foreign investor does not rank high on that list, but there has not been explicit criticism or action against their interests.

Generally, I would prefer to pick great companies, sit back and trust in management, and be happy to be along for the ride. I don’t really have a choice as a lowly retail investor anyway.

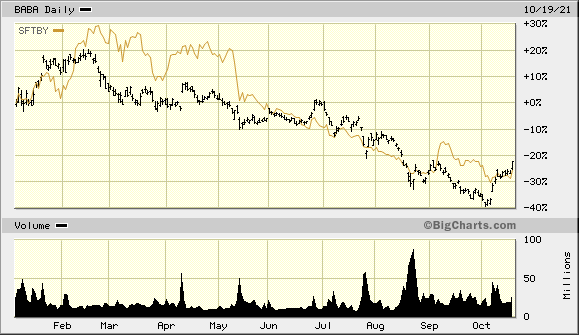

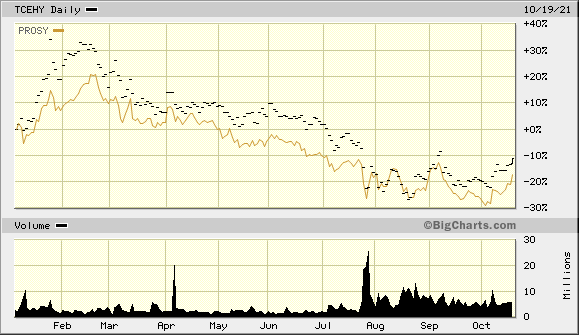

I own Alibaba / Softbank as well as Tencent / Prosus. I hold the ADRs as well as the Hong Kong shares, though I’m somewhat indifferent as both represent VIE ownership. If the U.S. were to ban Chinese trading, then I’d have to unload the Hong Kong shares anyway. Softbank and Prosus come with relevant correlated exposure to Alibaba and Tencent for tax loss harvesting, avoids the U.S. regulatory risk, and also come with intriguing emerging market Internet venture portfolios.

This is just my opinion. China has become uninvestable for many investors, who have a China-At-No-Price attitude. That thinking has helped them avoid the recent carnage. I believe the downside risks are already reflected in the stock price.

Famous last words perhaps.

I am intrigued by the odds, so lots more words follow below.

1. Alibaba and Tencent are incredible businesses with unfair advantages that trade at an attractive price.

A lot has been written on these companies.

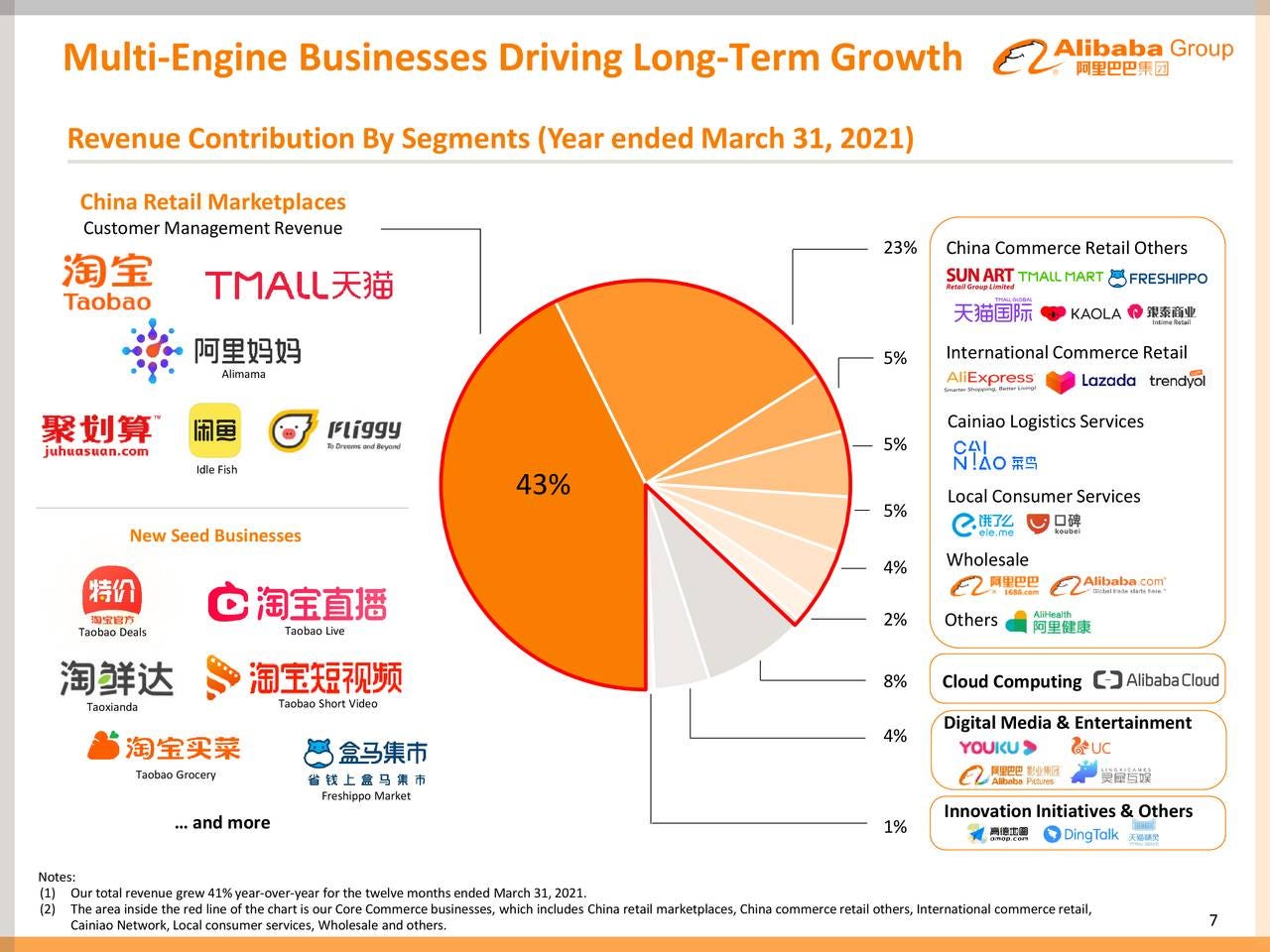

For Alibaba, Rob Vinall’s H1’21 letter has a good overview of the business and assessment of the regulatory impact. The starting point is their core marketplaces business, annual active consumers of 1.1B, GMV of $1.2T USD, and average spend per consumer of $1,400 USD:

“The investment case in Alibaba is straightforward. Its core marketplaces business is a wonderful business. It is highly profitable with an underlying operating margin of 75%. It can grow without committing much incremental capital. It is protected by numerous entry barriers including a massive installed customer base, network effects, and a thriving ecosystem. And it is likely to grow in the low to mid-teens for the foreseeable future driven by the growth in online consumption in China.”

Additionally, there are a number of nascent businesses. Within commerce, there is a growing offline retail footprint, the Cainiao logistics network, the global cross-border business in AliExpress (China to the world), the B2B business that provides the gateway for international brands to reach China’s consumers (the world to China), and ownership of leading e-commerce players Lazada (Southeast Asia), Trendyol (Turkey), and a 30% stake in Paytm (India).

That’s on top of a sizable media portfolio, the leading cloud infrastructure business, and a 30% stake in Ant Financial.

Source: Alibaba FY 2021 earnings presentation

The New Retail initiatives are progressing. Alibaba is investing in infrastructure to support commerce across online and offline and spanning the spectrum of fulfillment, from on-demand / local business level to hypermarket to traditional hub and spoke fulfillment.

Source: Alibaba FY 2021 earnings presentation

These Fresh Hippo stores will be really neat to check out one day.

Alibaba will have the widest integrated commerce offering spanning offline and online, plus cloud, plus payments. They’ll touch just about every Chinese consumer as well as every global brand interested in selling to those consumers. Some of these initiatives might be unprofitable or may not work out, but the overall direction seems inevitable. It’s a combination of Amazon and Google’s advantages in the U.S.

See more here: CEO 2021 letter, Alibaba - bull and bear, New Retail (Bain)

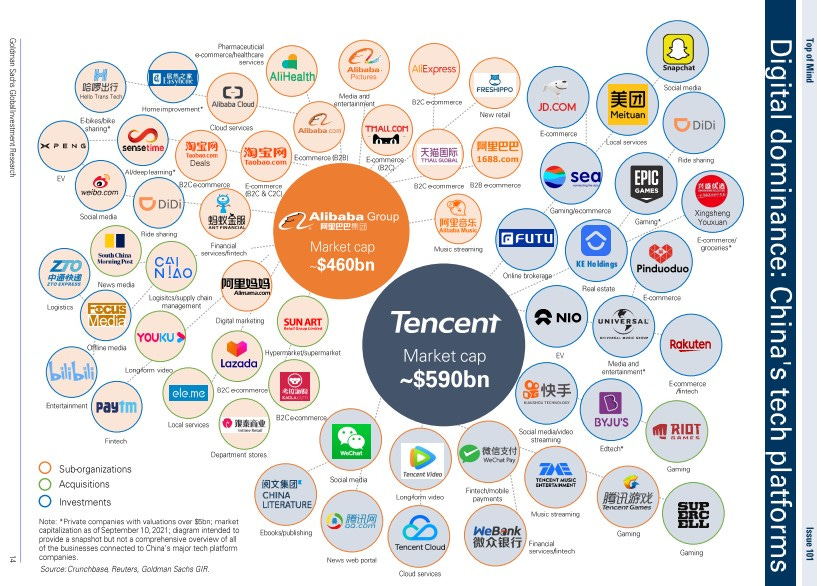

Tencent has two unfair advantages. The first is that they control distribution within entertainment (gaming). They either own the studios and properties outright, or they extract massive rents (up to 70%) from other publishers to distribute their games across China. The second is that their WeChat social media platform gives them the visibility and insights to cherry-pick the best emerging apps, take minority stakes in those companies, and then direct traffic to the anointed to supercharge their growth. This creates an incredibly powerful virtuous cycle: massive scale → data insights → informs strategic investments → traffic and engagement → more scale. This is as if Facebook and Apple were to collude to combine their data, traffic and distribution advantages to charge high take rates and build a venture portfolio. Where Alibaba controlled the choke point from a commerce perspective, Tencent controls the choke point from a content distribution and advertising perspective.

See more here: Compounder Fund thesis, Vineyard Holdings writeup, Tencent (Acquired podcast), Not Boring - Tencent and their investment portfolio

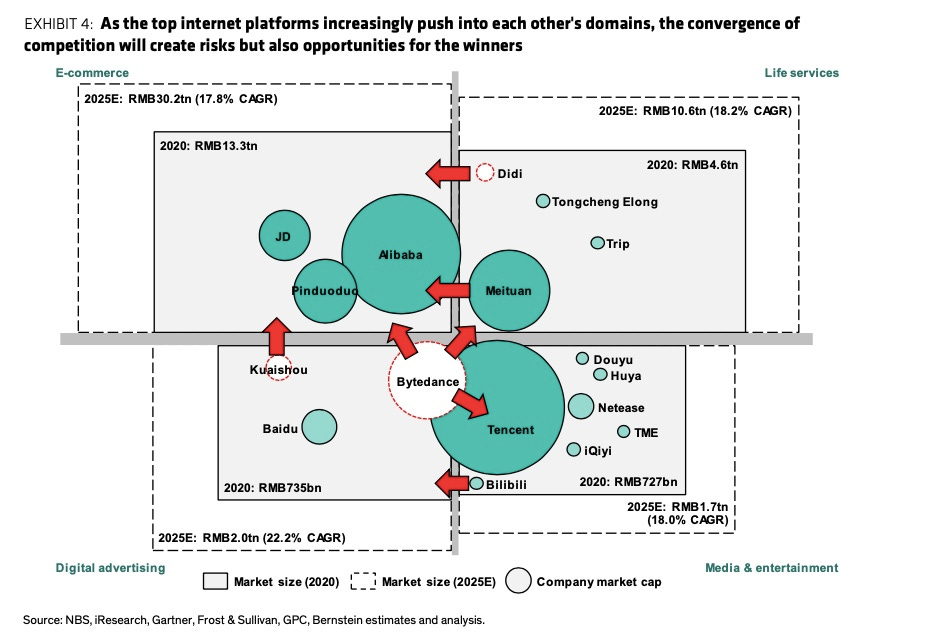

The below diagram showcases the immense ecosystems that Alibaba and Tencent have built, acquired or invested in. Emerging companies would need to choose, whether explicitly or implicitly, in which ecosystem to operate.

Source: Goldman Sachs, Is China Investable?

The CCP may have reasserted their monopoly on monopolies, but I think you can still have quite a valuable business on the back of a duopoly.

The market has been rattled though. China tech stocks have lost $1T in market cap so far this year and now trade at significant discounts to U.S. peers.

Source: Goldman Sachs, Is China Investable?

2. China regulatory actions on balance appear to be a net positive in the long term.

My take is yet another uninformed opinion.

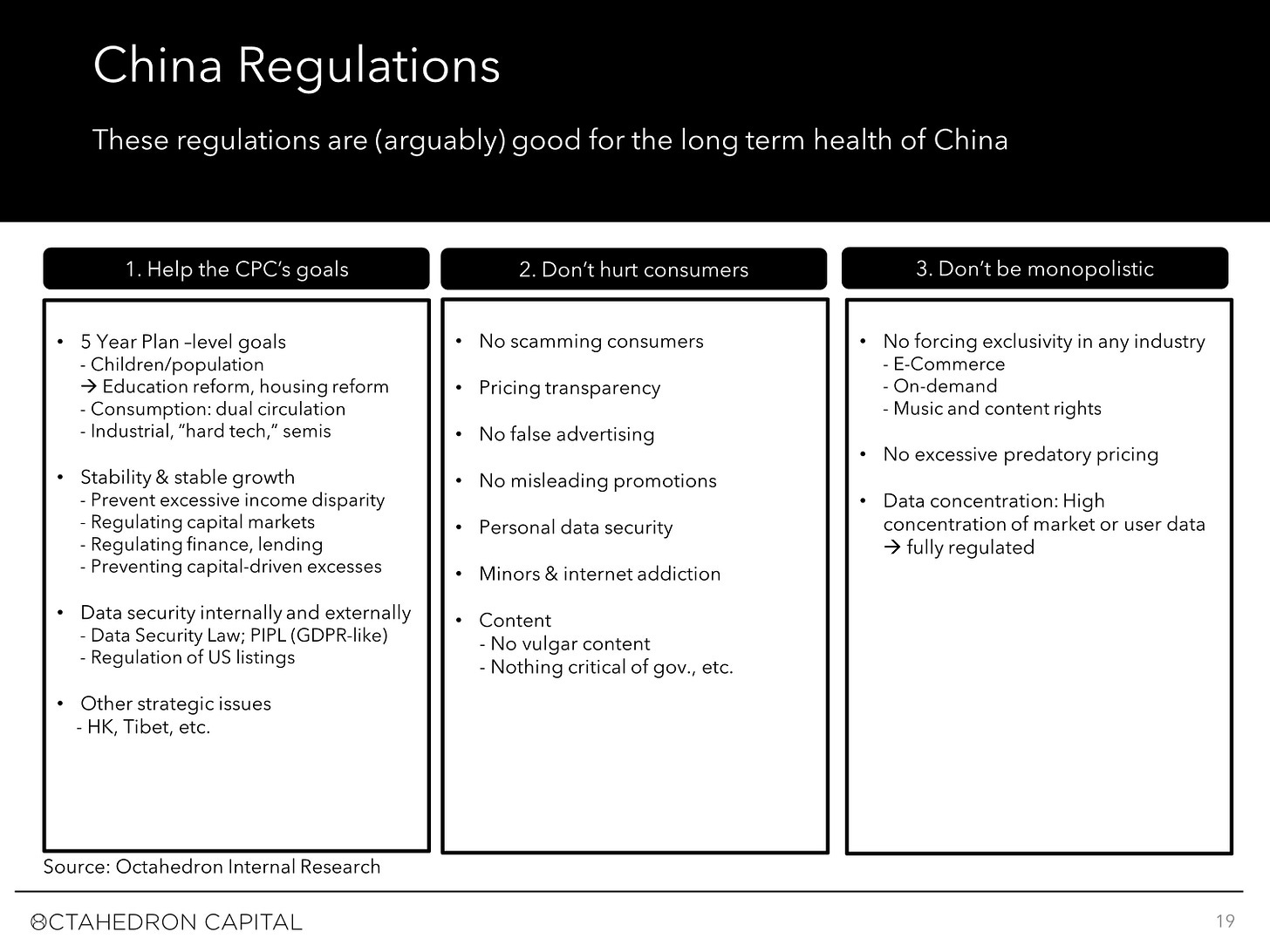

To me, the regulations are reasonably consistent with their stated goals, unlikely to alter China’s long-term aim to encourage foreign investment, and will probably benefit the incumbents in the long-term.

A. The CCP is doing what they said they were going to do.

In the last national congress (held every 5 years) in 2017, President Xi Jinping issued a report that outlined the following themes:

Remain true to our original aspiration and keep our mission firmly in mind, hold high the banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics, secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects, strive for the great success of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era, and work tirelessly to realize the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation.

Last year, Xi declared that 2021 would mark the beginning of a “new development phase,” one that would privilege national security, common prosperity, and social stability over unfettered growth.

The government’s sweeping crackdown on Big Tech (more specifically, on 平台经济 “platform economy” companies) is consistent with that vision.

Moreover, the Internet giants have increasingly become de facto infrastructure that operates beyond the government’s oversight and control.

As The Information’s Shai Oster puts it in this podcast:

"What Alibaba and Tencent have done is created national banking infrastructure. In China, national infrastructure is a national security. It's like highways, it's like power. And if huge amounts of your economy are being transacted behind closed doors effectively, through a private enterprise, that's not okay for the Chinese government."

For a government that prizes these attributes and above all control, after witnessing Internet platforms around the world grow their power, particularly in having outsized influences in election outcomes and the ability to expel sitting presidents from their platforms, it’s no wonder that they would act.

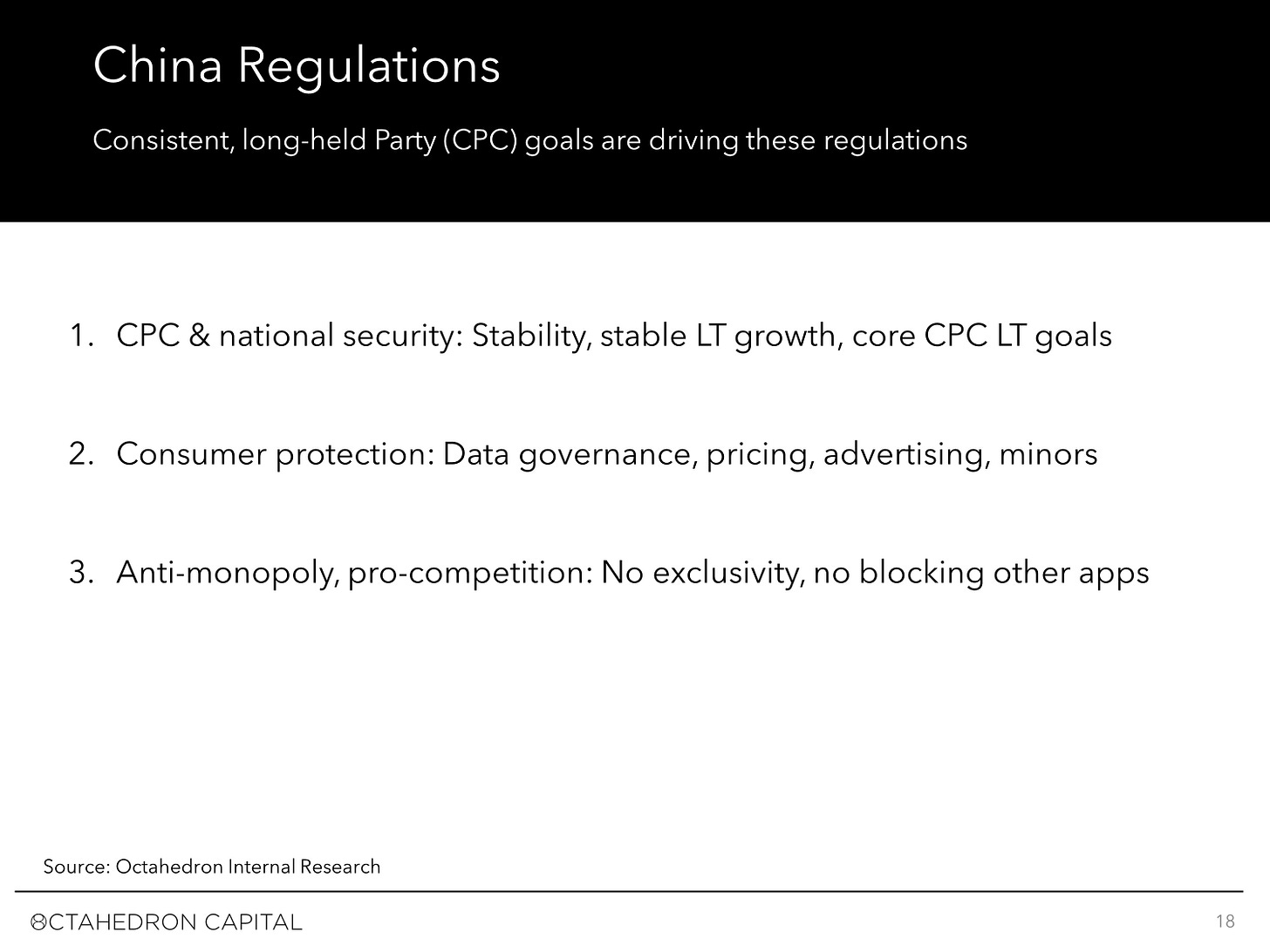

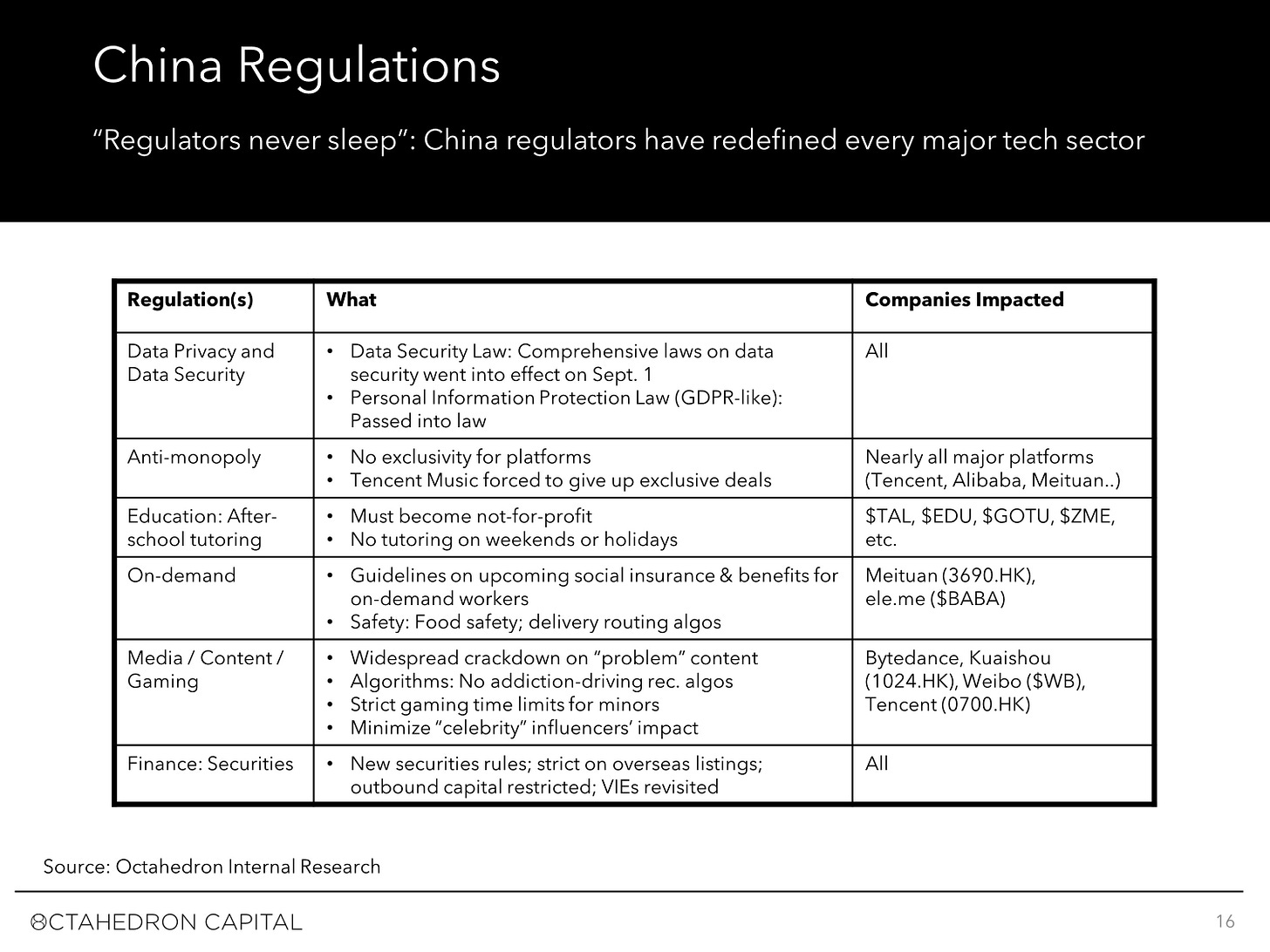

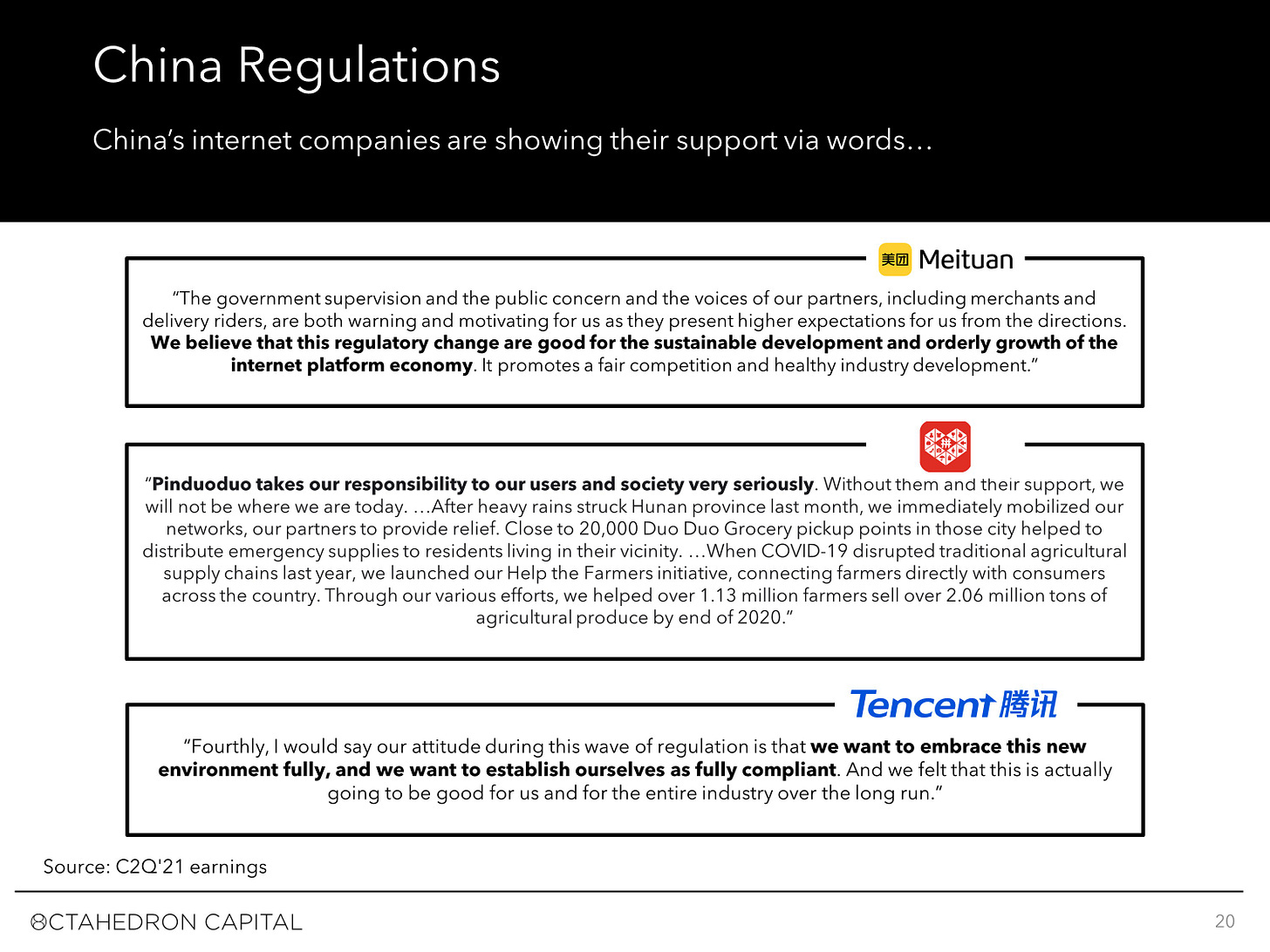

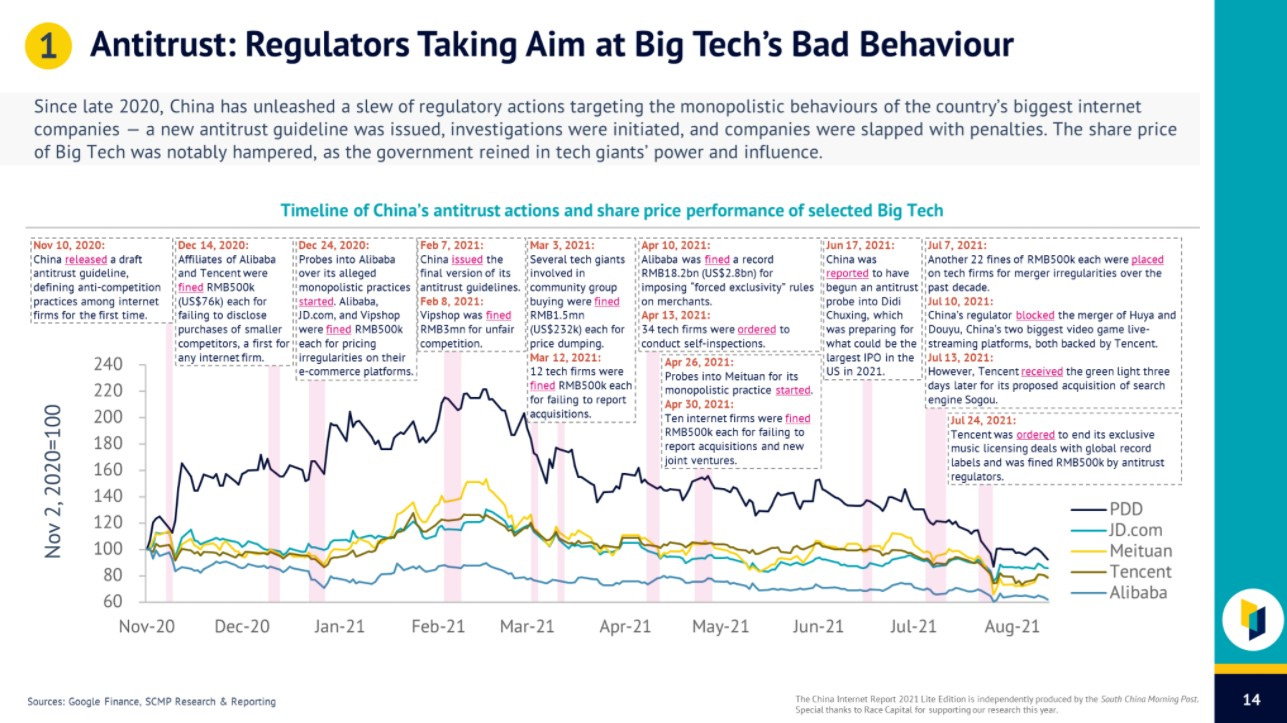

Octahedron Capital published A Few Things We Learned in 2Q’21 that summarizes the key goals and regulations that have been introduced (so far).

Given that backdrop, it probably was not entirely unexpected that the regulators would act. The speed and ferocity in which they acted, however, is another matter.

(and almost fanatical devotion to red uniforms and the CCP).

These two points capture China’s thinking:

She expands on this in a post regarding Huang Qifan, an influential central government policy advisor, regarding the main problems with consumer Internet companies. In summary,

“the lack of regulation and pure, simple greed has made it go awry, and so the costs are now outweighing the benefits, when you consider all stakeholders, not just shareholders. The "reckless expansion of capital" … is really about how irrational investment and abusive practices have wiped out any efficiency gains from technology, and are instead hiding unviable business models that do not add anything long-term to the economy.”

The actual regulations against the Internet platform companies have been aligned to these goals.

Source: Octahedron Capital, A Few Things We Learned in 2Q’21

As Rob Vinall wrote, the intended regulatory outcomes matter because:

“the apparent consensus in the West that the goal of regulation is to turn the clock back on capitalism. The intent is clearly to strengthen the market economy, not dismantle it. In the words of the Chinese government, the aim is stable, high-quality growth, not just fast growth.”

The regulations themselves may very well be a roadmap for what Western countries ought to consider, as the concerns that China has regarding the Internet platform companies are shared globally.

B. Dealing with the government is the normal course of business.

Chinese companies cooperate and comply and will adapt to the new environment. It’s an essential core competency and perhaps even a competitive advantage.

Shai Oster remarks how Tencent’s government relations team always seems to be a step ahead of the industry. They take prompt and decisive action, including the recent call to limit playing time by minors to 3 hours per week.

Government criticism regarding the ill effects of video games are hardly new. Tencent has been restricting playing time for minors for their games since 2017. In 2018, China froze license approvals for new titles for 9 months to combat games deemed illegal, immoral, low-quality, with negative social impact, and causing bad eyesight in children. 28,000 studios shut down in 2018 and 2019 due to these regulations, but then 22,000 new companies were opened in 2020.

That’s how it goes in China.

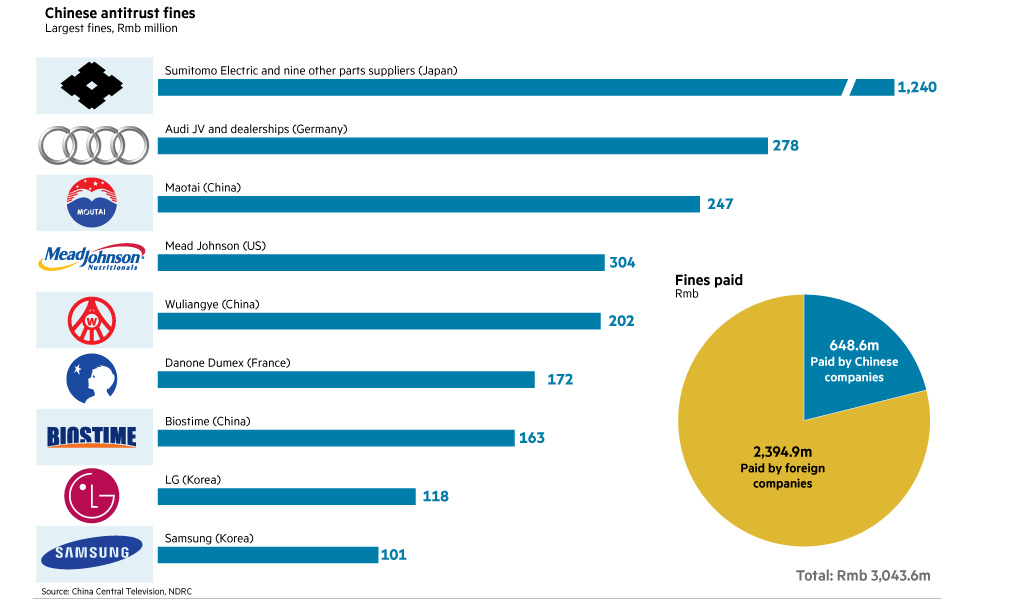

As an interesting aside, in 2014, the largest antitrust fines then levied by China had actually been against foreign firms, primarily in the auto space for price fixing. It has hardly made a dent in their appetite to participate in the China market. Keep pushing until you hit the boundaries, then stop.

Source: Synergistics Limited, China’s antitrust fines for foreign car companies fail to stall growth, Financial Times

Tencent president Martin Lau, on the Q2’21 earnings call from August 2021, addressed several questions related to the evolving regulatory landscape (transcript), highlighting four key points:

Internet regulation is a global trend. China is just leading the way.

Regulators are focused on identifying and rectifying industry misbehaviors and establishing regulations, with emphasis on compliance, social responsibility and fair and proper behavior.

Government wants to foster long-term sustainable development and healthy growth of the Internet. They recognize the economic and social importance of the Internet.

Tencent intends to embrace the new environment fully. They will be fully compliant. That has always been their attitude, and they believe they are well positioned to do it. They feel it is good for them and good for the industry in the long run.

Alibaba shared a similar position in their earnings call (transcript):

We believe all these new regulations aim to foster the healthy development of the Internet industry over the long run.

We will fulfill our responsibilities as a platform in accordance with the regulatory requirements and continue to carry out our commitments to be a good company that creates long-term value for the society in China and globally.

C. This is the new cost of doing business

It seems each passing week brings another set of penalties.

Other than the for-profit education industry, the penalties levied on the Internet platform companies so far have been manageable. The two most significant have been:

Meituan (October 2021): $533M fine, or 3% of revenue

Alibaba (April 2021): $2.8B fine, or 4% of revenue

Other examples were for price dumping related to community group buying (March 2021, ~$230k), for failure to disclose merger activity (March 2021, ~$75k), and for illegal monopolistic behavior related to M&A (July 2021, ~$75k), but these have been at a very minor scale. Hardly a punishment it seems. Fetch…the cushions!

More impactful to the bottom line will be the government ending preferential tax rebates. Alibaba, for example, forecasts an effective tax rate of 20% in Q3’21, up from 8% a year ago.

To end these rebates seems like a reasonable evolution given these companies are now fully grown and enjoy such a dominant position.

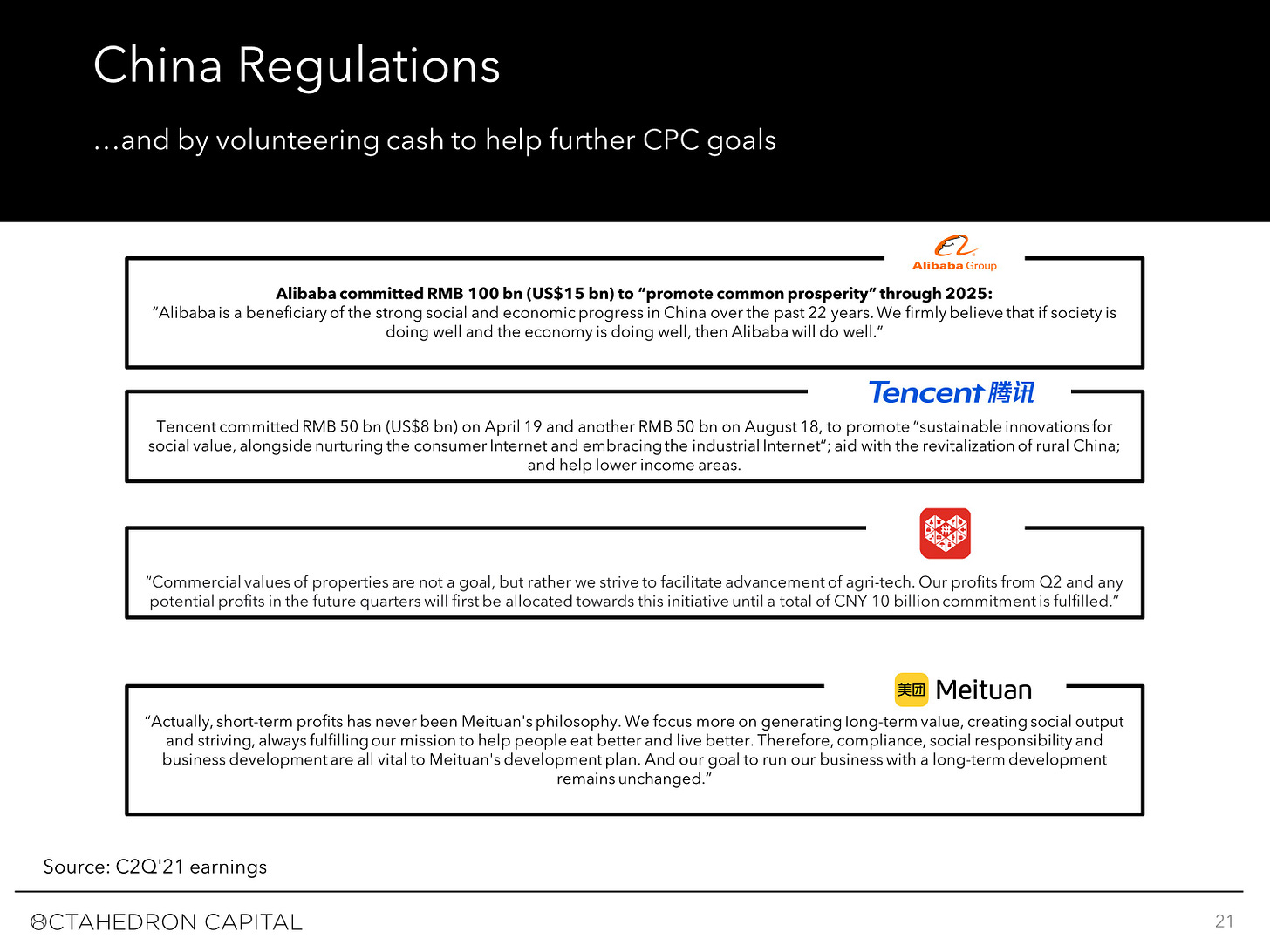

As for the (in)voluntary contributions to common prosperity initiatives, the companies are in near unison in their vociferous support of these measures.

Source: Octahedron Capital, A Few Things We Learned in 2Q’21

In my view, these fund flows, whether in the form of fines, increased taxes or mandatory common prosperity contributions, are all simply a form of transfer back to the government. In totality, it does not appear to be overly burdensome. The fines can be absorbed, the tax rate is still reasonable, and the societal contributions may very well help their business by supporting their stakeholders - a more intentional form of marketing spend.

D. Winners keep winning

A big focus of regulation has been the removal of exclusivity provisions known as 二选一 (“Two Choose One”) whereby dominant online platforms banned suppliers from working with competitors. It is part of greater antitrust actions, which include banning anticompetitive practices such as discriminatory pricing and bundling.

While this benefits the consumers and small businesses that depend on these platforms, I think these developments will help the incumbents’ competitive position relative to potential new entrants. They already enjoy entry barriers from their massive scale, network effects, and ecosystem. Now pile on burdensome government regulation and capital advantages as access to the U.S. financial markets is halted and prospective investors are deterred from this sector.

The U.S. tech giants do not have explicit exclusivity constraints on platform usage - most ecommerce sellers, for example, do not sell solely on Amazon - but that has not impeded their irresistible march toward dominance.

While there are no shortage of competitive threats, I would much prefer to be one of the larger circles in the below chart. A new dot would have a tremendous uphill climb ahead of it. Apart from Bytedance and Kuaishou, all of the other significant players already fall within the Alibaba or Tencent spheres of influence.

Source: Bernstein, via @briefnorris tweet

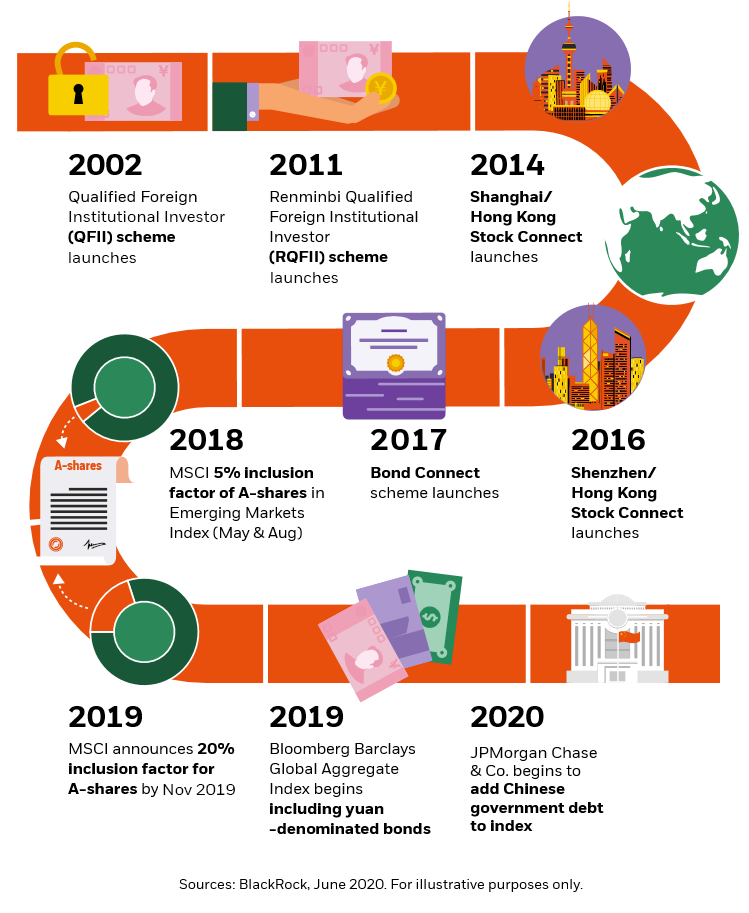

E. Directional arrow of progress still points to China opening markets

China regulatory actions have so far been directed domestically, and not at the international business community.

Ray Dalio provides context, explaining that while there are risks and opportunities, the overall direction of China’s actions to develop their capital markets, support entrepreneurship and encourage open foreign investment has never changed.

China certainly needs the help, as the WSJ points out:

China’s financial system “can charitably be described as a mess. It’s dominated by state-owned banks that constitute an enormous economic sinkhole. They soak up the prodigious savings accumulated by Chinese households, for which the banks pay almost no interest. They then divert the bulk of that money into ultracheap loans to state-owned or politically favored companies.”

“This leaves the country’s genuine entrepreneurs, who run productive small and medium-sized enterprises in the private sector, scrounging around for capital in a vast gray market of loosely regulated moneylenders, complex bond products and creative trade-finance arrangements.”

Xi Jinping has been consistently reassuring the international business community for years now (see 2015, and in 2020).

“China is ready to significantly reduce restrictions on foreign investment”

“Without reforms or further opening up, there will be no progress.”

More recently, other party members have offered the following (WSJ):

Fang Xinghai, (vice chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission): “China has no intention to decouple from global markets, and especially from the U.S.”

Fang: “The government is reviewing so-called variable interest entities…but it sees VIEs as a necessary and vital part of how Chinese firms engage with global markets.”

Liu He (Vice Premier): “China is trying to balance development and security. Doing so meant protecting competition and consumers, and this would be good for smaller companies.”

Indeed, the trend over the past few decades has been China opening up its markets to the rest of the world.

Source: BlackRock, China: The Essentials

In spite of the trade war rhetoric between U.S. and China, the two countries signed a trade deal in early 2020 that removed barriers for U.S. financial institutions to expand in the China market. BlackRock won approval to offer mutual funds to individual investors in China. Fidelity and JP Morgan have also set up wholly owned mutual fund units in China. Invesco is looking to manage part of China’s $400B national pension fund. Goldman Sachs got approval to own 51% of a wealth-management joint venture with Industrial & Commercial Bank of China.

Foreign investors have certainly sustained significant collateral damage from China’s regulatory actions. But it hasn’t slowed international companies from continuing their pursuit of the Chinese consumer.

China is prioritizing establishing the right set of ground rules to promote healthy growth over the near-term returns and concerns of international investors. It’s been painful to be sure, but it’s an understandable and perhaps justifiable set of growing pains. If you believe their pointed rhetoric against the Internet platform monopolists, then it seems reasonable to also believe that they intend to continue down the path of opening markets.

F. Tiger parents and golden children

The dream for “national rejuvenation” is made reality by showcasing the premier Chinese technology companies to the world.

In 2015, tech executives from leading U.S. and Chinese companies met with Xi Jinping in Seattle in his first American visit.

Source: Silicon Dragon Ventures

Cue the snark.

These companies were once the superstars and the pride of China who are now being reprimanded. I don’t believe sentiment has shifted such that they would be intentionally crippled.

Who represents China at the leading edge of tech? Who joins for the next photo shoot? While China is understandably concerned about maintaining control, they do want their companies to be successful and exemplary.

Tiger parents think they know what is best. They can certainly be overbearing.

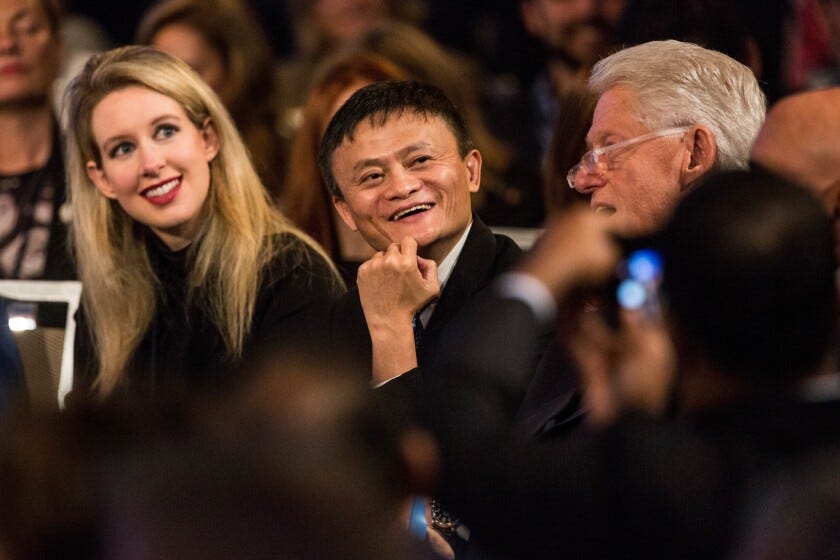

Jack Ma has infamously laid low for the past year, sparking intense speculation about his whereabouts and serving as a cautionary tale. He seems to have recently resurfaced, though there had been accounts of him taking up oil painting earlier in the year.

Few recall he’s already quite accomplished in that domain, having already sold one of his works for charity in 2015.

That was such a different time, as the below photo shows.

Source: LA Times, Alibaba founder Jack Ma sells his own painting for $5.4 million

G. VIE risk remains, though arguably declines as CCP scrutiny increases

The challenge with the variable interest entity structure for Chinese companies is that it is based on inconsistent statements. To investors, the company says that it owns its operations, but to Chinese regulators, they say that the business is owned by Chinese and not by foreigners.

The Chinese government has historically turned a blind eye to it even though it could theoretically declare the structure illegal and refuse to enforce the VIE’s contracts at any time. Meanwhile, the sector has relied on this structure while continuing to grow tremendously.

The hope was that China would eventually allow private Chinese companies to directly list abroad and eliminate the need for a VIE in the first place. That’s unlikely to happen.

China has made it a lot tougher for Chinese companies to go public overseas, which will be subject to review for data security prior to IPO. This has led to several IPOs getting cancelled.

Paul Gillis, expert on all things China accounting related, explains that he doubts that this is the end of U.S. IPOs for Chinese companies. China still wants access to foreign capital markets but will want control of the process. To achieve that, they will likely maintain the VIE, even though the structure itself has always been on shaky legal ground. He believes that it may actually be good for investors since companies that receive approval for listing will also receive the first official (indirect) sanctioning of the VIE structure.

H. Is this flurry of regulatory activity all just political positioning?

Some speculate that this explosion of regulation is really due to government officials positioning themselves in advance of the next national congress in October 2022, which happens every 5 years.

“Chinese regulators engage in turf wars, too, as they jostle to expand their influence,” notes David Wertime of Protocol. For example, China's powerful State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) was likewise established in 2018 to end rivalries among three antitrust agencies.

Although a lot has happened in the past year, it’s not over yet, as regulations are expected to continue rolling out through 2025.

Source: South China Morning Post, China Internet 2021

Shai Oster, however, theorizes that a lot of this activity is driven by the proximity of the next national congress, slated for October 2022.

The context for that event is that Xi Jinping will likely be elected to another 5-year term, breaking the term limit precedent, and possibly setting the stage to rule China indefinitely. For a party member, it will be a particularly critical time to be well positioned. As such, there is a mad scramble among the party as this period comes to a close to demonstrate their accomplishments and loyalty. Performance review is coming soon and this is their last chance to make an impression. “No mid-ranking bureaucrat will be punished for overreaching to demonstrate their commitment to Xi Jinping thought.“ Oster suspects that things will quiet down starting approximately 6 months prior to the congress.

Perhaps the CCP and the typical tech monopoly are not so different after all.

If so, the optics matter, and the bark will probably turn out to be worse than the bite. This seems generally consistent with the magnitude of the fines discussed earlier.

I. Scale economies shared, mandated by the ultimate activist

I’m a big fan of Nick Sleep’s philosophy of scale economies shared as a source of enduring competitive advantage. Costco and Amazon are the most common examples of companies that bolster their competitive positions in this way by giving back to their customers.

In a way, all of this regulatory activity forces Alibaba and Tencent to share their scale benefits across their stakeholders. It may be painful in the near-term, but it likely strengthens their longer-term positioning. It does not appear that the government has been specifically targeting Alibaba and Tencent since these regulations have been applied broadly.

China’s motivations appear to be grounded in control, national security, and broad prosperity. Driving down valuations in the near-term are merely a side effect. If that were to be sustained, then that would detract from their goal of opening up markets and being an attractive place for investment.

Overall, I believe these actions will create tremendous value while resetting the balance of power among the various stakeholders. Among the Internet platforms, I think that Alibaba and Tencent will continue to be the best positioned to reap this value. China may very well be doing these companies a favor with their regulatory actions.

3. U.S. regulatory and trade war related actions are a concern.

The U.S., in contrast to China, has been openly threatening to cut off Chinese access to American financial markets. This is where the greater risk lies in my view.

A. China may be the last bipartisan issue left in Washington

Anti-China sentiment is popular in the U.S. From concerns over the growing military power of China, to China’s “authoritarian capitalism”, to its spotty human rights record, to widespread suspicions about China’s role in the provenance of COVID-19, it is popular to blame China.

As NBC notes, “The issue brings together every wing of American politics, from progressive populists to ‘America First’ nationalists to traditional security hawks.”

“Our relationship with the PRC will be competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, and adversarial when it must be. The common denominator is the need to engage the PRC from a position of strength,” a U.S. State Department spokesperson told Al Jazeera.

As it relates to Chinese Internet companies against this backdrop, the potential pain to investors comes in the form of trading bans and blacklists.

B. PCAOB: a Chinese-sounding American regulating body

Sarbanes-Oxley required that all accounting firms be inspected by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the U.S. audit regulator, at least every three years. This includes foreign accounting firms.

Typically, companies that fail to meet disclosure requirements are delisted. The stock is then removed from a major U.S. exchange to a lower tier market in one of the over-the-counter categories (OTC). It’s less liquid and less prestigious, but still tradeable. In fact, there are approximately 10,000 OTC securities according to Schwab.

China has pushed back on these audits for two reasons: (1) they consider allowing a foreign regulator to enforce foreign law on Chinese soil to be an infringement of China’s sovereignty, and (2) they are concerned that audit work papers may contain state secrets (which basically includes any transaction with a China state owned enterprise, such as a mobile phone bill).

There are also new disclosure requirements that must be included in the issuer’s annual report. This includes the percentage of the company owned by foreign government entities, and whether any entities have a controlling financial interest in the covered issuer. Specific to China, the issuer must also disclose each official of the CCP who is a member of the board of directors.

There seems to be an attitude that because Chinese companies won’t submit to PCAOB audits, that this is a clear sign that they are cooking the books.

In fact, SEC Chair Gary Gensler recently wrote an WSJ opinion piece calling out China and Hong Kong for not allowing the PCAOB to “audit the auditors,” a key component of Sarbanes-Oxley.

Paul Gillis explains that many countries, not just China, initially resisted allowing the PCAOB to come to their countries to inspect their books citing similar concerns.

The Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act in 2020 goes even farther, however. Rather than simply delist, it prohibits trading in an issuer’s stock if a foreign jurisdiction prevents an inspection by American regulators for 3 consecutive years. That puts Chinese companies on track to be banned from trading in the U.S. in 2024, and possibly earlier.

While certain companies may indeed be fraudulent, I suspect the vast number would follow their standard government relations playbook and just comply. The dilemma is that they’ve been caught in the crossfire of competing and conflicting regulatory mandates between the U.S. and Chinese governments.

There may be more to come, as the U.S. could simply take a stricter position on Chinese companies. For example, the U.S. could force delistings of VIE companies, full stop. It used to be that Chinese companies would go public in the U.S. via reverse merger by acquiring shell companies, but that practice has since been restricted.

With China unlikely to allow additional regulatory scrutiny of its companies, and the SEC affirming its intention to enforce the laws, it seems likely that an inevitable wave of trading halts and delisting orders is coming.

C. Making a blacklist, checking it twice

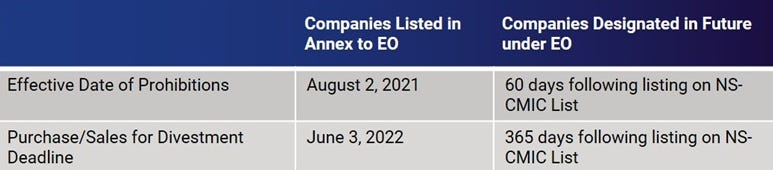

The U.S. has a number of national security blacklists that may implicate Chinese companies. This Akin Gump article provides a useful summary, which relates to restrictions based on concerns of those companies’ relationships with the Chinese military.

The two of note are the Entity List and the Communist Chinese Military Companies CCMC list (which changed over to the NS-CMIC List in June 2021). The Entity List is an outright ban restricting American companies exporting technology to Chinese firms, as well as restrictions on trading in those companies’ securities. The CMIC list prohibits trading of the companies’ securities, though generally investors have a year to sell.

Notable companies that are included on these lists include Huawei, SMIC, and Xiaomi. When Xiaomi was added to the CCMC list in January 2021, its share price declined ~10%.

SupChina’s excellent guide and timeline on China’s tech crackdown suggests that investors should lean toward sectors that align with China’s strategic goals such as AI, semiconductors, 5G, advanced manufacturing and green energy. However, that might be problematic for U.S. investors if those sectors also happen to be caught in U.S. blacklists.

It could potentially extend to Internet platform companies as well. In late 2020, the U.S. had already contemplated blacklisting Alibaba and Tencent, which would prohibit Americans from investing in them. Further, they were going to ban TikTok and WeChat amid concerns of user data security and potential Chinese surveillance risks, a decision that was later reversed by the Biden administration in 2021.

Alibaba’s recent foray into chip design to support their cloud business is both great news from a business perspective, but also not-so-great if it increases U.S. blacklisting risk. If the key to failure is trying to please everyone, then better, I suppose, to improve positioning with Chinese regulators by graduating into the “real” tech of semiconductors.

Some investors advocate swapping their holdings in Chinese companies from U.S. ADRs to the Hong Kong stock exchange. Alibaba ADRs have this conversion right embedded. That, unfortunately, won’t help if these companies are placed on a U.S. blacklist.

D. What happens in a trading ban?

As a practical matter, it’s not the end of the world if a trading ban were to take place. There would still be a period of time, potentially up to a year, for U.S. persons to divest those securities. The rules keep changing, but the below reflects the latest.

Source: Lexology, Biden Revises Ban on U.S. Investors Buying Certain Chinese Securities, June 2021

For U.S. investors in China, the risk from U.S. regulatory activity is meaningful, and potentially more so than from China.

4. Western companies may not be immune and risks appear to be underappreciated

While Chinese companies have seen their share prices crushed in recent months, Western companies have been relatively unscathed. Some may interpret that as further evidence of capitalism’s superiority over communism. It’s unclear to me whether that is warranted under the circumstances. It seems to understate several risks and suggests that investors may be taking the following areas for granted.

A. Companies have continued access to Chinese markets

Despite the escalating trade war rhetoric, it doesn’t seem to have materially altered the strategic importance of China to Western companies.

Many companies point to tapping the Chinese consumer as a critical priority and growth area. Think Apple, Tesla, Nike, GM and Starbucks.

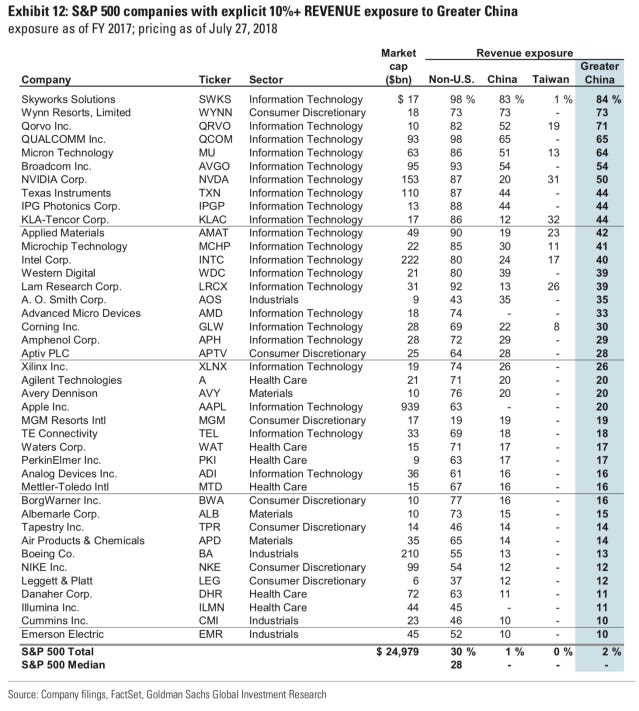

The below slide is a bit dated and admittedly not from the most reputable source, but I think the point is still valid. There are a lot of S&P companies that depend on China for a significant portion of revenue and growth.

Source: WallStreetBets

A lot depends on the whims of the U.S. and Chinese governments.

Certain sectors, such as semiconductors, derive a significant portion of their revenue from China. If battle lines were to be drawn, it seems probable that these companies would get pulled in.

Going back to the Xiaomi example, the article notes that since Xiaomi was not included on the Entity list, its commercial relationships with American suppliers such as Qualcomm were not impacted (as of yet). Qualcomm did suffer a drop after Huawei was sanctioned, but it would seem their business is far more vulnerable to regulatory action than the Chinese companies.

Not to be outdone by the U.S., China has also introduced a blacklist - the Unreliable Entity list (不可靠实体清单规定). No specific companies have been identified yet. Rather, only broad guidelines were described, implicating companies that would endanger Chinese national sovereignty, security or development interests, or discriminate against a Chinese entity.

This was widely seen as a preparation for potential Chinese retaliation on U.S. companies,

“a potent weapon in the escalating trade war [in reaction to actions taken against Huawei and TikTok)…Analysts have suggested that U.S. companies such as Apple, Tesla, and FedEx might have the most to lose if they end up on the receiving end of Chinese sanctions.“

Foreign companies worry that they are about to become “sacrificial pawns in a game of political chess.”

American market indices don’t seem to reflect this risk to the same extent as Chinese stocks.

B. Chinese-style regulation will not or cannot happen here

Western media such as the Economist generally cast China’s regulatory activities in a negative light.

They criticize the crackdowns as “China’s regulatory immaturity on full display,” the work of just “50 or so people” that will “likely prove self-defeating,” as it will “raise suspicion abroad,” hamper their ambitions to set global tech standards, and “dull the entrepreneurial spirit within China."

However, they also acknowledge that these policing actions were overdue and that China’s moves,

“echoes concerns that motivate regulators and politicians in the West: that digital markets tend towards monopolies and that tech firms hoard data, abuse suppliers, exploit workers and undermine public morality.”

These concerns are not that different from what FTC Chair Lina Khan wrote about in her seminal paper, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, which observed that the current consumer welfare doctrine underappreciated the risks of predatory pricing and anticompetitive vertical integration. The two approaches to address this were:

Promote competition by breaking up or preventing mergers within industries where dominance is apparent.

Accept dominant online platforms as natural monopolies or oligopolies and seek to regulate their power instead, with the most common forms being: (1) requiring nondiscrimination in price and service, (2) setting limits on rate-setting, and (3) imposing capitalization and investment requirements.

It’s not that different from what China has been doing already.

Interestingly, Facebook in particular has cited China as an argument for why they should not be regulated or broken up. As this 2018 Recode interview put it in the headline, “Mark Zuckerberg says breaking up Facebook would pave the way for China’s tech companies to dominate.” That argument seems less convincing now.

Indeed, the FTC filed an amended complaint in August against Facebook (the first was dismissed in June), alleging they had illegally acquired innovative competitors Instagram and WhatsApp and burying successful app developers. The agency is now seeking to unwind those deals. This is in contrast to China’s response, which was to slap weak fines across the entire industry.

Based on share prices, the market seems to take a dim view toward the prospects that U.S. regulators will be effective in prosecuting its antitrust cases against the Internet giants. It may even think that a potential breakup would unlock additional shareholder value to offset any negative impact.

That may be accurate for the time being. Entrenched interests are powerful and well funded, the government is increasingly polarized and ineffective, and the tech companies are staying combative and defensive. But it wouldn’t be for a lack of effort on the part of regulators. If the companies keep testing the limits, the U.S. may very well be one inflammatory speech away from reach a tipping point similar to what China experienced last year.

C. Continued superiority of U.S. capital markets

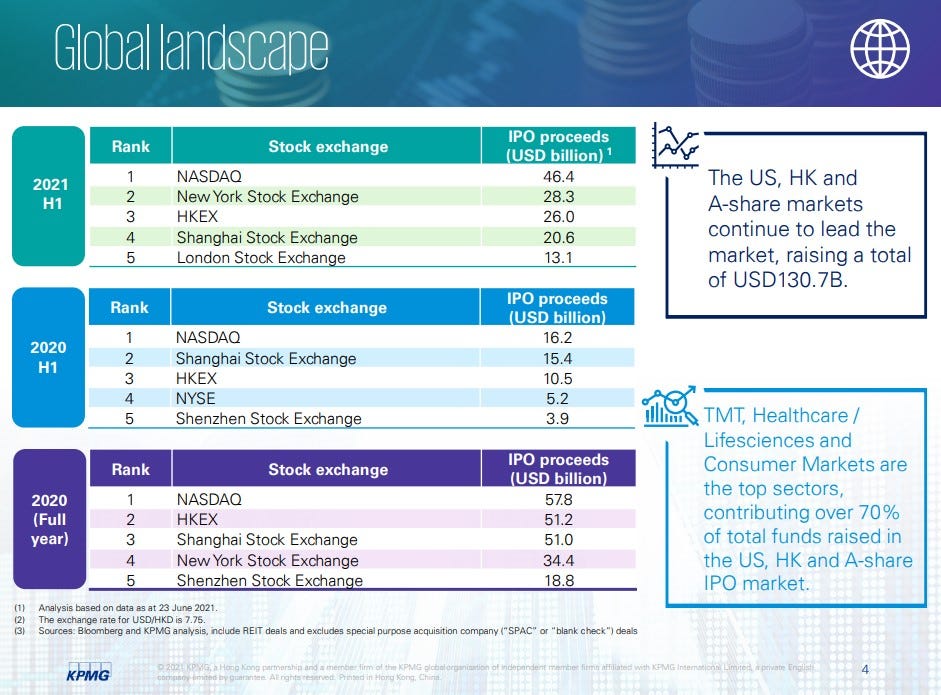

Quick, how much larger are the NASDAQ and New York Stock Exchange compared to Hong Kong and Shanghai?

Source: KPMG, Mainland China and Hong Kong IPO markets 2021 mid-year review

The gap in H1 2021 is much narrower than I would have expected. I would not have predicted the 2020 rankings at all.

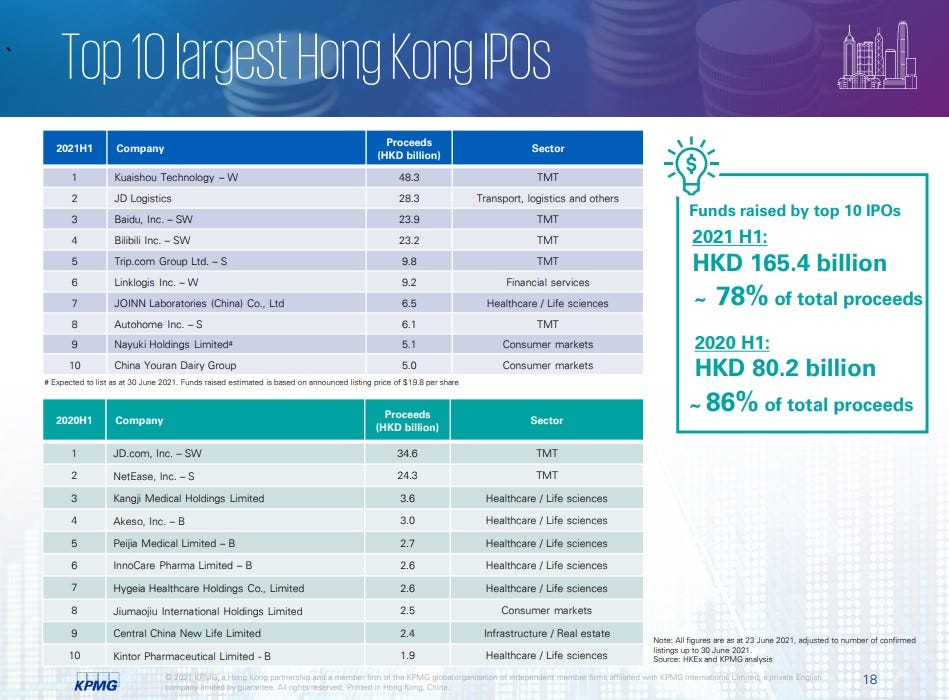

Hong Kong in particular is becoming a top listing destination.

Source: Fortune, Chinese tech IPOs fuel Hong Kong stock exchange’s best first half ever

I found these statistics startling. My impression has long been that U.S. capital markets are indisputably the premier destination for listed companies. Recent relative market performance between the U.S. and China would suggest the triumph of American capitalism. While generally still true, it seems the lead may not be quite as wide as I would have thought.

When Alibaba went public as the biggest IPO ever in 2014, it famously chose to do so on the New York Stock Exchange rather than Hong Kong. The company clashed with Hong Kong regulators over their refusal to relax its one-share-one-vote stance to accept Alibaba’s shareholding structure that permitted the insiders control of the majority of board seats. When Alibaba decided to pass, this was widely perceived as a loss for Hong Kong.

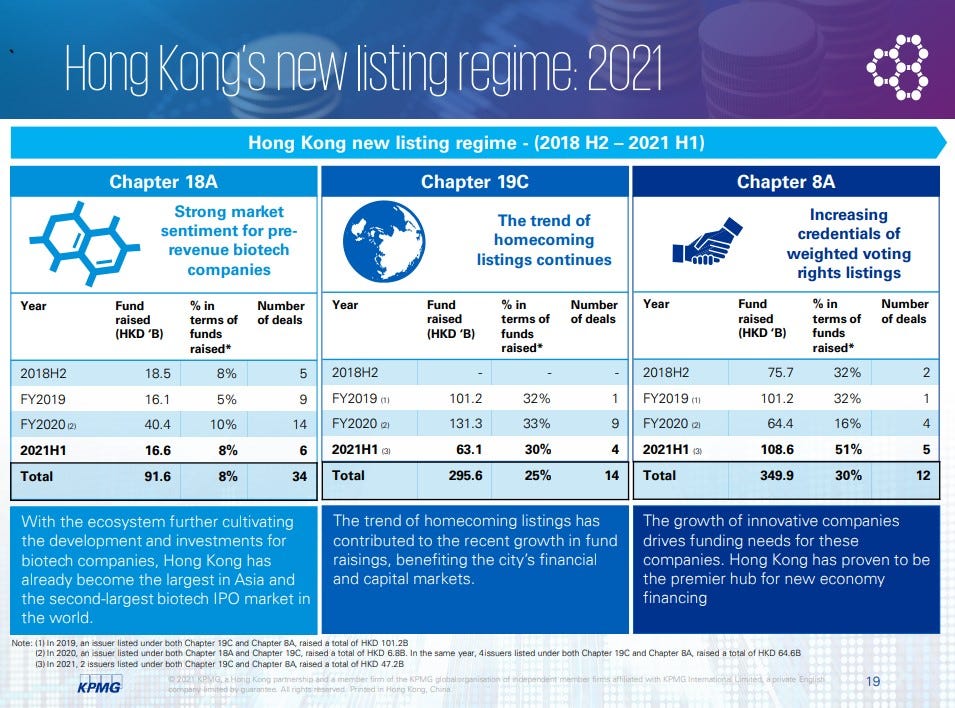

It turns out that Chinese tech companies often chose to list in the U.S. not only to tap into a broader and more sophisticated investor pool, but also because they simply didn’t qualify to list on Hong Kong and China exchanges. They were often tripped up by their “weighted voting rights” (WVR) structures and lack of profitability. Ironically, VIE structures were also subject to a lot more scrutiny, whereas they were permissible in the U.S.

This boils down to the core difference in how these markets operate:

China and Hong Kong: Regulators review and approve

U.S.: Disclose the risks, and let the buyer beware

In this way, U.S. exchanges allow unprofitable, pre-revenue, VIE shell companies with multiple share classes to go public. Some tech companies such as SNAP and GOOG float share classes that do not even have voting rights. The U.S. has its own share of fraudulent companies, and SPACs seem to be an American phenomenon.

Hong Kong has since relaxed their standards to compete for new listings, but it’s standards are still more strict than the U.S. Alibaba did eventually list in Hong Kong in 2019.

That change has marked the beginning of a homecoming trend for Chinese companies across industries, and it’s starting to show up in their IPO volume statistics:

Source: KPMG, Mainland China and Hong Kong IPO markets 2021 mid-year review

I wouldn’t be too alarmed for the future of American capital markets. Most investors trust a company listed in the U.S. than listed elsewhere, and that is unlikely to change. These recent Hong Kong offerings have also been primarily dual listings.

The point is that perhaps I shouldn’t automatically assume that a U.S. listing bestows a seal of quality, or that it will always stay the premier listing destination. Paying attention to the activity in Hong Kong seems worthwhile.

D. The longer-term effects of sanctions for the U.S.

In his 2020 letter, Dan Wang wrote that the effect of U.S. sanctions against Chinese companies has forced them to pursue domestic alternatives.

“By withholding components that Chinese companies have relied upon, the US government has turned American firms into unreliable suppliers. Chinese companies have responded by de-Americanizing their supply chains because they have no choice.”

He expands on the unintended consequences for the U.S. companies. On the one hand, it aligns the interests of Chinese tech companies with the CCP.

Hardly any of China’s largest technology companies have escaped some form or threat of US sanctions, and many more are wondering if they will end up on some poorly-understood blacklist. Thus the US government has aligned the interests of China’s leading tech companies with the state’s interest in self-sufficiency and technological greatness.

It also weakens U.S. companies.

“US politicians can observe the sometimes-devastating impacts of sanctions. What they don’t seem to realize—or want to believe—is that they’re simultaneously pummeling the American brand writ large. I’ve documented for Dragonomics the uncomfortable questions American companies tell me they’re starting to face on whether they can credibly be long-term suppliers.”

Overall, it’s hard not to come to the conclusion that these activities may ultimately be self-defeating.

“At a time when it’s more important than ever to advance its semiconductor companies, the government is crippling their sales to their largest or fastest-growing market. When research capabilities at US universities need to grow, the government is denying them students. And when the US should be attracting more talent to its shores, the government has made it more difficult for people to immigrate. Thus the US looks committed to a strategy of destroying the scientific and industrial establishment in order to save it.”

Conclusion: Zoom out

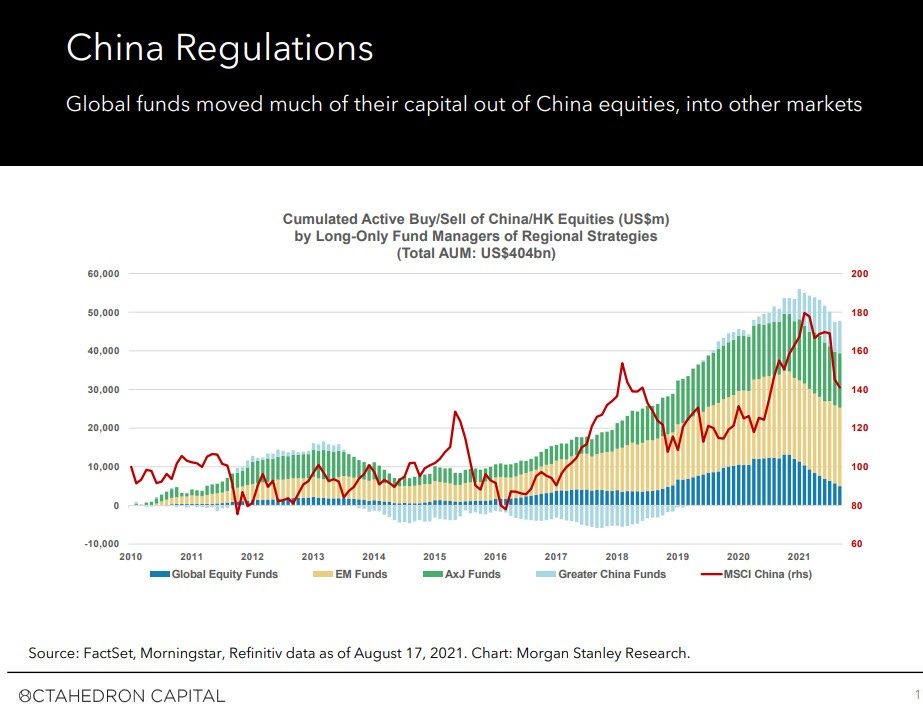

The last year has been brutal. Institutions have been shifting funds out of China until the dust settles.

Source: Octahedron Capital, A Few Things We Learned in 2Q’21

Zooming out on that chart, 30-50% drawdowns for China seem to be the norm and happen regularly every few years.

This time around, the culprits are draconian government regulations and a looming Evergrande default. Compare that to the narratives surrounding previous declines:

2018 - Chinese markets’ 2018 performance was their worst in a decade

“Beijing’s ongoing trade war with Washington dominated headlines for much of the year…Even before the escalation in trade tensions with the U.S. this year, Beijing was already trying to manage a slowdown in its economy after three decades of breakneck growth…’The toolbox is becoming emptier and emptier’

2016 - U.S., world stock markets slide as panic in China spreads

“Against a backdrop of a weak economy and, some argue, an overvalued currency, confidence in China had long been in short supply. But investors also blamed the panic here on ill-considered and poorly explained moves by the authorities this week.”

2013 - China ends year as Asia’s weakest market

“China may be the world’s fastest-growing major economy, but it can also lay claim to a more dubious superlative: home of the worst-performing stock market in Asia.”

There are good reasons to be skeptical, but haters gonna hate.

What am I missing?

A possible outcome is that there will be risk of ruin, or at least forced selling, as a result of unanticipated regulatory activity or escalating trade war hostilities. This doesn’t go away, but I believe the probability is low. The specter of catastrophic regulation hung over many disruptive technology companies such as Uber and Airbnb, which has faded to a distant memory now.

A slightly more likely outcome is that the business models of the Internet platforms have been permanently impaired. As stated earlier though, I don’t believe this to be the case, and I think the incumbents will come out just fine.

The most probable outcome is that China continues to progress and modernize, Internet platforms shrug off these latest mandates, and Chinese markets continue to open up to global investors. Choppiness is to be expected, but ten years from now, I can’t help but think that the indices will be much higher, and the leading companies much larger and more valuable, than they are today.

In fact, the one area that might be overlooked given all the doomsday news is underestimating the power and resiliency of the Internet platforms.

For the long-term holder, the odds would indicate an opportune time to build a position. To me, the price already reflects the risk. Shares have already started to recover a bit since I started writing this article (many weeks in the making now).

For me, it’s all sort of mechanical at this point. It’s the time of year when I appreciate the correlations between Alibaba vs. Softbank and Tencent vs. Prosus. It’s not perfect, but it’s close enough. The venture portfolios (Softbank, Prosus) are also a welcome addition.

Alibaba vs. Softbank (2021 YTD) - BigCharts:

Tencent vs. Prosus (2021 YTD) - BigCharts:

BlackRock has recommended investors raise allocations to China by two to three times, saying that China should no longer be considered an emerging market. That would suggest China’s weighting of 4.2% in the MSCI All-World index should be raised to above 10%. It makes sense to me, even though it feels really really hard to do.

Is this a strong buy opportunity, or a clear signal to sell? As Scott Galloway would say, the answer is yes. His below tweet likely confirms whatever you already believe.

*** Note: For entertainment and informational purposes only. Not investment advice. Please do your own research. ***